With the help of someone who got

in touch via this blog I recently found the identity of my 5x great

grandfather, John Davis of Little Missenden in Buckinghamshire. I don’t know

John’s religious denomination, but the area of Buckinghamshire around Little

and Great Missenden was one of the earliest centres of non-conformist dissent

in England.

Many of my earliest known

ancestors from the region around Buckinghamshire and Hertfordshire were devout

non-conformists – Quakers and Baptists. Two of John Davis’s granddaughters married two

Salter brothers: John, and my 3x great grandfather Samuel Salter who was a

deacon of the first Baptist Church

in Watford, Herts who bought a £100 share in the

dissenters’ university, London University.

Two more of John and Samuel’s brothers also embodied the family’s staunch

non-conformist tradition: William Salter gave the land for a Congregationalist chapel in Norwood, south London;

and David left money in his will for a row of four almshouses in Watford High

Street.

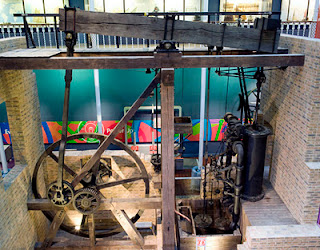

A typical late 18th century malting house and kiln

(this one at Burwell in Cambridgeshire)

John Davis was a maltster.

Malting was an important process, a key stage in the business of brewing beer.

In the days before a reliable clean public water supply, beer was the safe,

healthy option for quenching your thirst – everyone drank it – so malted grain was

in high demand and malting was big business (and consequently highly taxed by

the governments of the day).

What the maltsters did was to

convert the starch in grain crops, especially barley, to sugar which the

brewers of beer needed for the fermentation of their brew. This conversion was

achieved by soaking the barley in water and spreading it out on the floor of

the malting house, where it began to germinate.

The malting house was a long

building, and the maltster moved the germinating barley along the length of it

over the course of a few days with a shovel, turning the barley over as he did

so to ensure an even conversion by the time it reached the end of the

malthouse. In nature the germinating grain uses the sugar to sprout and grow;

to preserve the sugar for the brewer and prevent sprouting, the maltster next

roasted the grain in a kiln to the brewer’s specification. The brewer relied on

the skillful judgement of the maltster in producing the desired flavour of

malt: light malts for pale ales, darker malts for stouts such as Guinness.

The Malt Shovel, popular English pub name

recognises the importance of the maltster to the nation’s beer

(L-R: pubs in Sandwich in Kent, Harden in Yorkshire and Oswaldkirk in Northumberland)

Before I learned of John Davis, I

knew that his grandson-in-law Samuel Salter was also a maltster. Samuel came

from a long line of brickmakers, and the switch from bricks and mortar to malt

for brewing had intrigued me. I convinced myself that the family had at some

point taken their expertise in the technology of the kilns used to fire bricks,

and simply applied it to the process of roasting barley. But having discovered

a maltster ancestor two generations earlier than Samuel, I now have a different

theory.

As far as I can tell John had

only two male Davis grandchildren,

one of whom emigrated to Australia

– so there was certainly room in the Davis

malt business for new blood. Samuel on the other hand was the youngest of five

sons, and unlikely to inherit a share or even a role in the Salter brickmaking

business. It seems likely therefore that his entry into the malt industry was a

direct result of his marriage in 1800 to John Davis’s granddaughter Sarah,

a dowry in the form of a business opportunity.

Samuel certainly took to his new

trade with enthusiasm and an eye for innovation. In 1808 he took out a patent

on “an apparatus for the purpose of drying malt, hops or any kind of grain.”

And his eldest son, also Samuel, followed him into the business. His youngest

on the other hand followed the other family tradition: William Augustus Salter,

my great great grandfather, went to the university which his father helped to

found, and became a Baptist minister.