The Verralls of Lewes in Sussex

The White Hart Inn, Lewes

Coffee houses arrived in Britain London London

When Richard died young only eight years later, his brother Henry (my great aunt’s 3x great grandfather!) took over the running of it. Henry kept the coffee house for over 40 years, and must have been at the centre of the town’s gossip and political debate, hosting the radical movers and shakers of the day in his shop. One such radical was a certain Tom Paine, an excise officer from Norfolk who was posted to Lewes in 1768.

Tom Paine’s house in Lewes, 1768-1774

Thomas Paine involved himself in local politics, and also campaigned for a pay-rise for his fellow excise officers – he himself had to pad out his income by running a tobacco shop in Lewes. Henry certainly knew him, and it is reported that one day, after a game of bowls, they repaired to the White Hart for a bowl of punch. As the drink flowed Verrall quipped, in reference to Frederick II of Prussia Britain King of Prussia was the best fellow in the world for a King, he had so much of the Devil in him.” Paine apparently subsequently reflected that “if it were necessary for a King to have so much of the Devil in him, Kings might be very well dispensed with.”

Memorial plaque on the wall of the White Hart Inn, Lewes

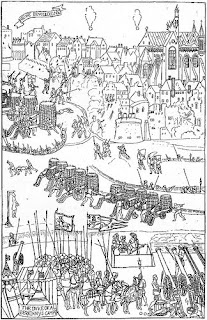

In 1774 Paine was sacked from his job in Excise and met Benjamin Franklin in London North America . There he became known as the father of the American revolution because of the radical ideas he published in a pamphlet called “Common Sense” in 1776. He returned to Britain

A descendent of Henry’s (the writer Edward Verrall Lucas, not me!) was thus able to claim that Thomas Paine, the driving force behind the two greatest political events of the age, had been inspired by a casual remark over punch in the pub by Henry Verrall. Although that may be a little unlikely, it does seem a distinct possibility that Paine’s ideas were honed in the talking shop that was Verrall’s New Coffee House in Lewes.