This marks the third

anniversary of Tall Tales from the Trees, for which I wrote the first article

on 29th

November 2009. 170 postings later, thanks to

everyone who has popped in, for the more than 74,000 page views. I still try to

bring history into focus by looking at the little things, the ordinary people

who lived through it. By and large my ancestors didn’t make history; but

like everyone else’s ancestors they were there when it happened and their lives

were shaped by it.

Take my 3x great uncle Charles. Unremarkable

man: Bristol solicitor, Liberal campaigner, would-be MP, local

militia man, landlord and letter writer. He left no particular mark on the

world, unless you count the memorial lectern given in his name to his local

church after his death. What he did leave was his portable writing-case, on

which he drafted his letters and in which he stored items of correspondence

received of professional and personal significance.

Captain Charles Castle

(1813-1886)

letter writer and

traveller

From my late uncle John I inherited not the

case but its contents – 120 letters from the 1830s to the 1860s with unique

glimpses of his public and private life. News from those who had emigrated to Australia, tensions within the family at home, business failures – I’ve drawn on many of them for articles here. In

addition, it contained his passport, which he obtained in a great hurry along

with several visas for his honeymoon in 1861.

Stuffed inside the pass book were four loose

visa documents from earlier trips to Europe, probably made in connection with a wine

importing venture in which he was involved for a while. Their dates, and the

differences between them, offer a very direct illustration of a transitional

period in European politics.

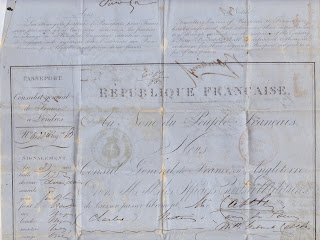

All are for travel in France. Here’s one from 1847:

And here’s one from 1850:

Spot the difference? The first is issued “Au

Nom De Sa Majesté LE ROI DES FRANÇAIS,” in the Name of His Majesty THE KING OF THE FRENCH; the second is from the “RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE, Au Nom Du Peuple Français,”

the FRENCH REPUBLIC in the Name of the French People.

In 1848, between the issue of these two

documents, the French political system underwent its second overwhelming

upheaval in just 60 years. The French revolution of 1789 swept away the Ancien

Régime, the old ruling class, and the First French Republic was proclaimed in 1792. A constitutional

monarchy (more accountable than the absolute rule of the pre-revolutionary

French kings) was returned to power in 1814. But a poor harvest in 1846, the

same one which produced the catastrophic Irish famine, led in France to food shortages, poverty and an

economic crash. In 1847, while Charles Castle was travelling in France, riots

broke out in French industrial towns, where unemployment ran as high as 60%.

Public assembly had been banned in France since 1835. Instead gatherings such

as funerals and weddings became the focus for crowds to hear dissident politicians.

This “banquet campaign” harnessed popular dissatisfaction in the second half of

1847, to the extent that two “banquets” planned for early 1848 were prohibited

by the prime minister François Guizot. The renewed rioting which followed that prohibition

led directly to a second French revolution, a coup d’état which overthrew

the king Louis-Philippe and established the Second French Republic – the republic

whose name appears at the top of Charles’s 1850 visa.

The reverse of Charles Castle's 1850 French visa

All four visas carry extensive stamps and notes

on the back, not only from France but from Prussia, Austria, Switzerland and Italy. Some of the 120 letters he kept

were posted to European addresses to await collection by Charles on his travels. One

day I will sit down to decipher all the marks, correlate them with his

correspondence and work out his itinerary.

The passports issued by the monarchy and the republic

are, it is worth pointing out, identical in every respect, except for the

addition after 1848 of a note at the top of the need for a Provisional Pass if travelling

into the countryside. It’s a nice case of “plus

ça change”! All of them include a description of Charles Castle’s

appearance – brown hair, brows and eyes; a high or open forehead, and medium to

long nose; a small to medium mouth; and a round chin and an oval face. His height

seems to vary between 1.87 before the revolution and 1.75 afterwards! (Perhaps as an imperial Englishman he was unfamiliar

with metric conversion.)

Charles’s visas were

not his only connection with the revolutionary events of 1848, which saw

challenges to the regimes of many European countries. Perhaps because of what

he saw in France, he was an enthusiastic supporter of the failed Hungarian revolution. When

its leader Lajos Kossuth came to Britain in 1851, Charles and his brother Michael drafted a petition in his

support which attracted 5585 Bristol signiatures, and

Charles received the personal thanks of the exiled politician. I have written

about the Hungarian connection here in the past. Another ancestor, John Salter,

was directly caught up in the French disturbances. A horticulturalist living in

Versailles, he had to flee France at short notice and return to London, where he promptly

opened the Versailles Nursery in Hammersmith. You can read his story here too.

Do you know if Charles Castle had any dealings with a Solicitor Called Jacob Crook in Bristol and Did they have any dealings with land for the Great Western Railway ?

ReplyDeleteHe did have some dealings with the GWR, via his involvement with teh Bristol & Exeter Railway. I don't recognise the name Jacob Crook, but I'll check the letters and see if he crops up. You can reach me privately via my website (link above right).

ReplyDelete